Make your APIs Discoverable with APIs.json

You’ve built a brilliant API, and you’ve taken the time to document it, but how do you get this API advertised to potential users? After all, the more users that discover your API, the more business you’re getting, so it’s worth thinking about discoverability beyond a tweet and a blog.

API Marketplaces like API Layer and RapidAPI let you list APIs in a searchable directory so potential users can find them. There are quite a few API Marketplaces, and they seem to come and go over time, which means adding every one of your APIs to every marketplace (and keeping it all up-to-date) can be outrageously time consuming. Years ago when most companies only had one API it might be an easy guess: https://example.org/api or https://api.example.org/, but as more and more APIs start popping up from different teams with mismatched creative codenames, keeping track of APIs can become more difficult internally and externally.

Many API teams have created “API Catalogs” to list their own APIs, which is often a hand-built system or using something like Bump.sh’s Hubs, so it feels like the most logical approach is to use your API Catalog to create a shareable directory of your APIs to other marketplaces and tools.

As with everything in the world of APIs there’s a brilliant specification for doing this, but as with everything it has a very vague name: APIs.json. Not to be confused with JSON:API, APIs.json is a specification that aims to solve API discoverability, created by Kin “API Evangelist” Lane and Steven Willmott.

How does APIs.json work? #

APIs.json contains two simple concepts to help software find your APIs and learn about them.

- a “Well Known” URL of

/apis.json(or/apis.yaml). - a specific JSON/YAML data format for that URL.

Think of the /apis.json URL like /robots.txt or /sitemap.xml. In the same way that various crawlers and automated agents will use that information to find out what should be indexed on a particular domain, the /apis.json URL can help various agents discover what APIs are available on a given domain.

The data for that endpoint looks a little something like this.

{

"name": "My Train Company",

"description": "## Welcome to the Bump.sh demo!\r\n\r\n*Bump.sh is much more than stunning documentation, for all your APIs.*\r\n\r\nBrowse through **API Hubs** and our **sleek documentation experience**. Try out our **search feature**, and discover how **Bump highlights changes** when you iterate on APIs development.\r\n\r\n[Signup](https://bump.sh/users/sign_up) to deploy your own API docs in minutes, and discover all configuration options and integrations.",

"url": "https://demo.bump.sh/apis",

"created": "2019-12-12",

"modified": "2024-05-16",

"specificationVersion": "0.16",

"apis": [

{

"name": "Train Travel API",

"humanUrl": "https://demo.bump.sh/doc/trainbook",

"created": "2024-05-16",

"modified": "2024-05-16",

"description": "API for finding and booking train trips across Europe.",

"version": "1.0.0",

"properties": [

{

"type": "x-access-level",

"data": "public"

},

{

"type": "x-definition-type",

"data": "REST"

}

]

},

// ... other APIs ...

]

}

There’s a lot to look at here, but basically there is some metadata about the collection of APIs, then an array of APIs. Let’s start with the top level properties that describe the collection itself, and this is based on v0.16 of the specification.

- name (required): text string of human readable name for the collection of APIs

- description (required): text human readable description of the collection of APIs.

- type (optional): Type of collection (Index [of a single API], Collection [of multiple APIs], Blueprint [of a new API]).

- image (optional): Web URL leading to an image to be used to represent the collection of APIs defined in this file.

- url (required): Web URL indicating the location of the latest version of this file so it can be more portable.

- tags (optional): a handful of key words and phrases that describe your API collection.

- created (required): date of creation of the file.

- modified (required): date of last modification of the file.

- specificationVersion (required): version of the APIs.json specification in use.

- apis (optional): list of APIs identified in the file.

The apis collection being optional feels a little funny, but APIs.json can describe a single API as well as a collection of APIs. There’s not many examples of APIs.json being used this way, so we’ll stick to using it for a collection of APIs.

- name (required): name of the API

- description (required): human readable text description of the API.

- image (optional): URL of an image which can be used as an “icon” for the API if displayed by a search engine.

- humanUrl (optional): Web URL corresponding to human readable information about the API.

- baseUrl (optional): Web URL corresponding to the root URL of the API or primary endpoint.

- version (optional): String representing the version number of the API this description refers to.

- tags: (collection) (optional): this is a list of descriptive strings which identify the API.

The humanUrl can point to some API documentation, whether that’s some hand-written guides, API reference documentation generated by OpenAPI, or anything else.

The baseUrl is where the API domain actually lives, so any robots seeing this APIs.json file can go off and start actually interacting with the API automatically.

The version could be the latest version of the API that’s deployed just so robots know things have changed, perhaps being more wary of a major version change, or using it to keep talking to different versions of an API.

Then tags appears on the API level, helping make clear that “Funny Name Our Team Liked API” actually handles ["payments", "contracts"].

You can build all of this yourself, or you can host your documentation with Bump.sh and let us do it.

Working with APIs.json in Bump.sh #

Bump.sh will automatically create an /apis.json for anyone using Documentation Hubs. Hubs are a way of grouping APIs with shared access controls, grouping together related or relevant API documentation. A Hub could be for a team, a department, or for a product line that has multiple APIs that all communicate with each other.

How you use them is up to you, but to work with APIs.json you’ll want to make a Hub.

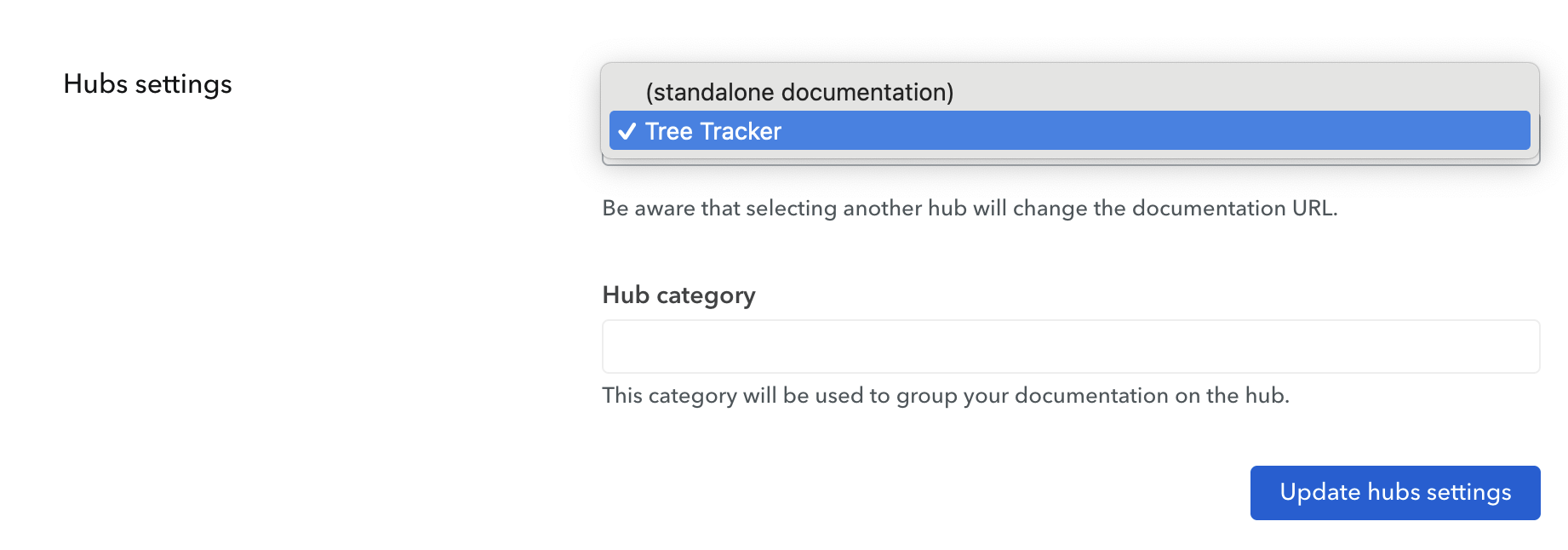

Then add some APIs to that Hub on the API’s Settings page.

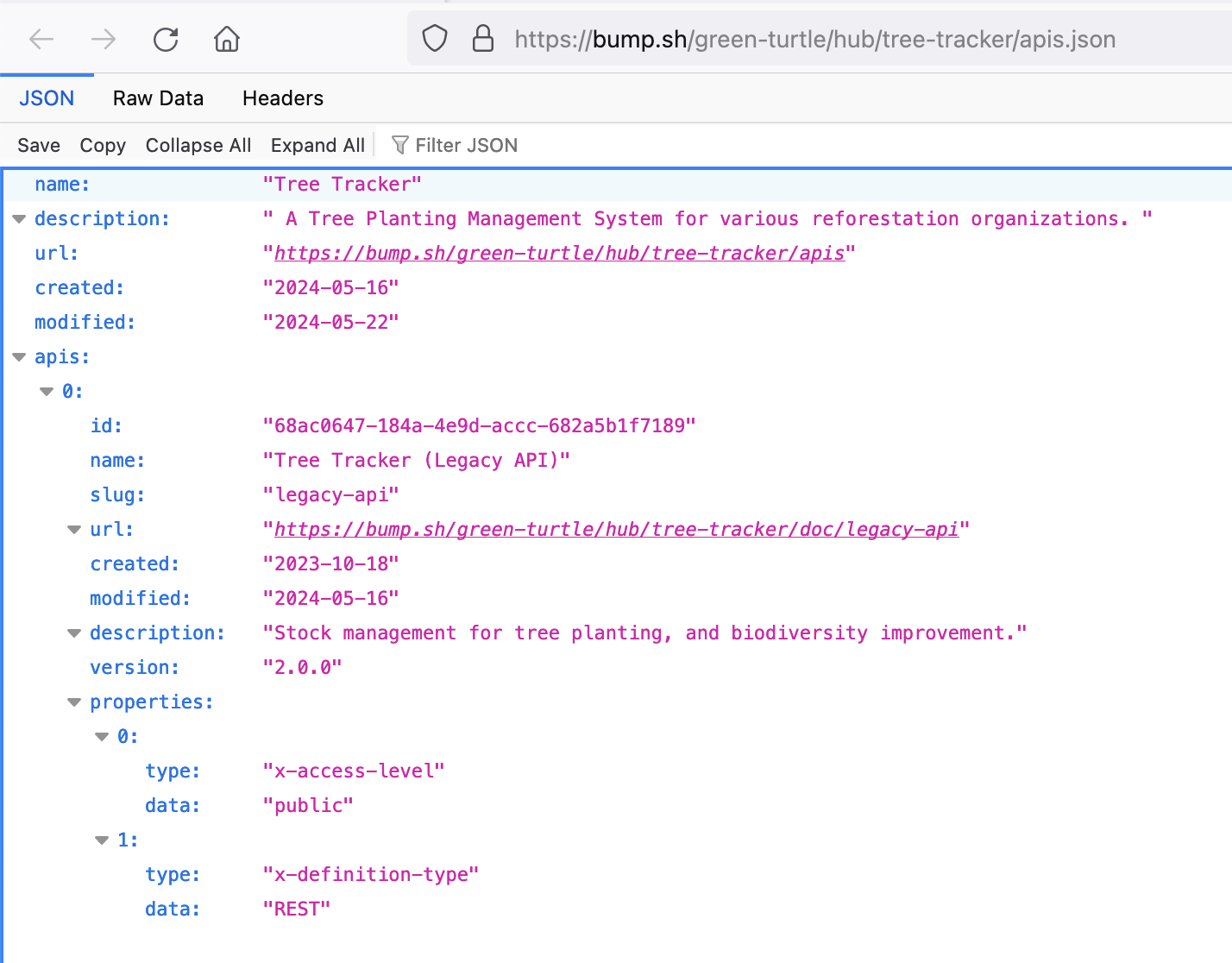

Now head over to the Dashboard and click View Hub, and you’ll be taken to a URL like https://bump.sh/<org-slug>/hub/<hub-slug>. To get the APIs.json endpoint you can append /apis.json onto the end of that URL, to produce https://bump.sh/<org-slug>/hub/<hub-slug>/apis.json.

Submit APIs.json to APIs.io #

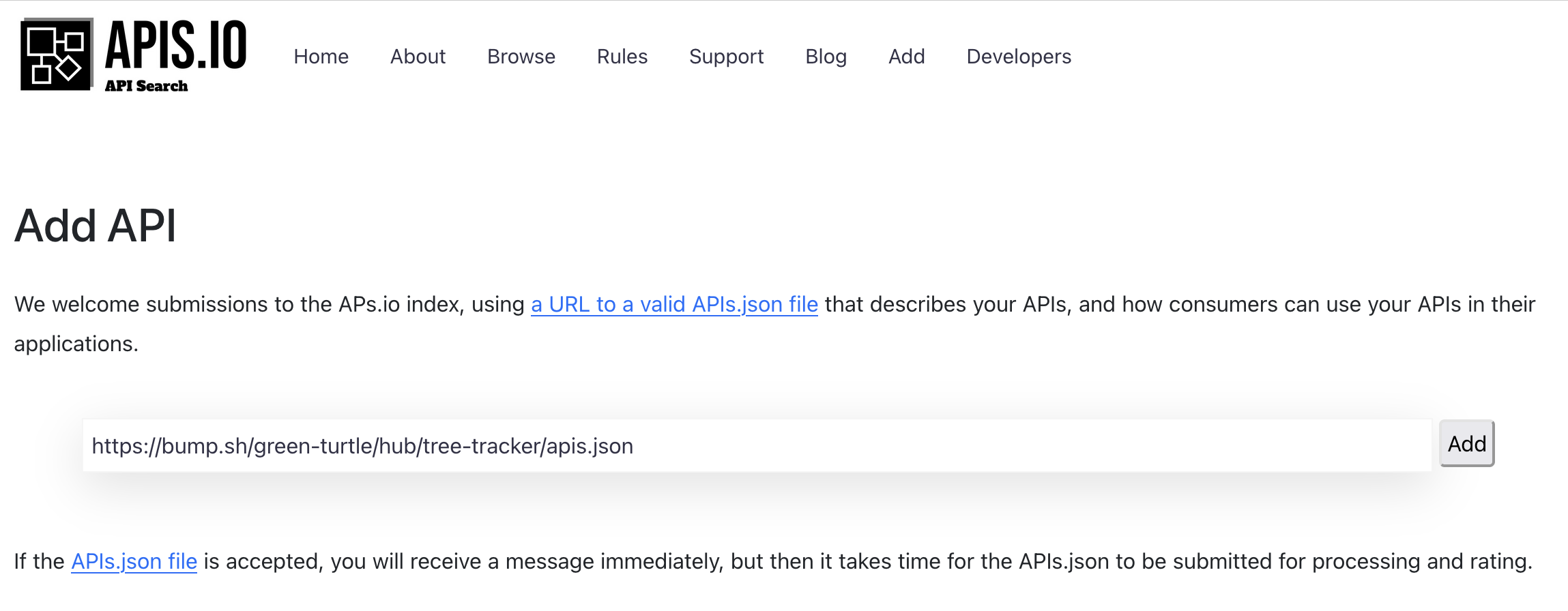

Great! Now, the first thing we should do with this APIs.json is use it to help people find our APIs by submitting our APIs to APIs.io, which is a new API Marketplace that describes itself as “the search engine for APIs”.

Head over to APIs.io: Add, and paste your link into the URL box.

If you want to automate submissions and updates then you can use the APIs.io API, or grab one of their SDKs, but it may well be easier to just submit the form.

Private Bump.sh Hubs #

If you want to make your hubs private but still want to access the data in APIs.json, then you can access it via the Bump.sh API using the Hubs endpoint.

curl -X GET https://bump.sh/api/v1/hubs/<hub-slug-or-id> -H "Authorization: Token <access-token>"

This makes it slightly trickier to pass to some software, but private things are definitively harder to discover. At least you can use this document for use-cases that involve code or CLI once you have it.

Other Uses for APIs.json #

APIs.json has been around for a decade, but is only starting picking up steam recently thanks to tooling starting to support it. Support is still limited, but there are countless potential use cases that can be handled with this specification.

Bump.sh customers are already using it for quality assurance on their developer portals, making sure all of their internal APIs are published, and available at all times. Using Continuous Integration they can check the generated APIs.json, and make sure their API documentation is there and visible on the expect URLs.

There are also clear implications for monitoring, if each API can advertise its /health endpoints you can pass that to monitoring software, or even just ping each endpoint yourself to look for downtime or issues listed in the health check.

The days of only have one API to manage are gone, and now we’re in an age of “API Sprawl”. Let’s all get better at keeping track of our APIs, helping end-users find documentation, support contacts, and any other information in a sensible scalable way, without having to rely on search engines or begging for help on social media.